In an earlier paper we discussed the benefits of incorporating a public health approach as healthcare providers build programs for population health management. We can use analytics to develop risk segmentations of our population and predictive models so we can target patients with personalized interventions. At the same time, we know that healthy behaviors can account for 30% of health outcomes, therefore, it is imperative that we find a way to engage and activate patients so that they have the knowledge, skills, and support to make behavior changes that will lead to better health.

There is much excitement in the health care industry around the topic of patient engagement. Organizations are implementing technology and collecting data through electronic medical records (EMRs) and patient portals. They now need to focus on developing patient engagement strategies and using the data from these (and possibly other) sources to get to the heart of the issue – moving patients toward becoming active and engaged managers of their health. Truly engaging and activating patients requires a shift in mindset to get beyond lamenting that patients did not do what we told them to do. Instead, healthcare providers need to have a better understanding of what makes their patients tick: an understanding of how providers can support health behavior change, and how to customize interactions with patients. Then providers will be better equipped to engage in partnerships with patients to successfully influence the way they eat, sleep, exercise, manage stress, avoid use of potentially harmful substances such as tobacco and alcohol, and take their prescribed medications.

Readiness to change

A popular behavior change framework, called the Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983[1]) has frequently been used to characterize the personal (and cyclical) process of improving health behaviors. The change process is illustrated in the figure below.

According to the Model, change begins with pre-contemplation – where the patient is not thinking about changing the behavior; it moves to contemplation – when the patient becomes aware of the problem and begins thinking about the possibility of change; next, there is preparation to change – making a decision to try to change (perhaps gathering some information regarding change options and resources); next, action –initiating a behavior change, which may be a small or a dramatic change; maintenance – this important phase of change addresses incorporation of the new healthier behaviors into daily life (i.e., healthier behavior becomes part of the lifestyle). The maintenance phase may continue for a very long time (years or entire life, in some cases), although it is possible that some adjustments or renewed efforts may be needed to continue to address the health need; it is not uncommon to experience a relapse into the prior unhealthy behaviors – which means action must be taken to cycle back through the change process. Additional support and change strategies may be needed to address a relapse; sometimes it is desirable to attempt a different approach/intervention to reach the goal.

Figure 1. Transtheoretical Model of Change

Stages of change can be applied to the current issue of engaging patients and working collaboratively for lifestyle change. We can learn much from the substance abuse treatment field in terms of how to engage patients to make lifestyle change. Alcoholics Anonymous ([AA], and similarly Narcotics Anonymous and Overeaters Anonymous) is a self-help group that uses a 12 step approach to changing unhealthy behaviors. The first step for addressing substance abuse is admitting that the behavior is a problem (e.g., reaching the contemplation stage). Similarly, we need to help patients accept that they must become owners of their own health and encourage them to become willing to critically examine their health risks and how their behaviors can affect their health status – including both immediate and long-term health outcomes. Some patients will be eager to discuss and possibly address health behaviors, in fact some may already be actively working toward a healthy lifestyle. Other patients may be very hesitant to provider inquiries into health habits/choices, so different approaches will be needed to build trust and engage these patients – they key is to examine change for which the patient is ready.

A patient may be ready for one aspect of change (walking the dog the around the block every day) and not ready to quit smoking. In this model, it is critical to work together with the patient in developing a “next step” around an area of change for which the patient is ready. This also means that stages of change are behavior-specific rather than person-specific. A person is not in a particular stage, but their behavior of quitting smoking may in pre-contemplation. At the same time, they may be in maintenance for alcohol consumption. A true partnership and collaboration in the change process is based on being clear about what the patient is and is not ready to address. If the conversation is truly patient-centered, focus on steps the patient is ready to begin.

Engagement and Activation to change

Providers in both the acute and ambulatory environments can play an important role in encouraging patients to actively manage their health. Dr. Judith Hibbard[ii] has demonstrated that interventions to improve patient skills and confidence in their ability to alter health behaviors, which she terms “Patient Activation”, can lead to better health experiences and outcomes. Activated patients also report higher quality interactions with their medical providers. Hibbard has done work on the importance of patients becoming actively engaged in their health and has developed measures that identify levels of activation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Levels of Patient Activation

A prerequisite of patient activation is engagement. Our communications and messaging to consumers and patients must evolve into a supportive partnership. Instead of unidirectional provider-issued directives basically prescribing a particular behavior change (e.g., you have got to quit smoking!), a collaborative, bi-directional message that arises from understanding patient health goals and perceived barriers to change is more likely to be successful. The emphasis of these provider: patient conversations is on patient-centered goal setting and the journey toward a healthier lifestyle is long and includes many incremental steps. Viewing the journey as incremental, with a focus on “progress not perfection” is more helpful than traditional provider messaging where the patient either is or is not “compliant”. For example, if a patient is averse to colonoscopy, there are alternatives that still help with colon cancer screening and cancer risk reduction; or if a patient is not confident that she can quit or reduce smoking due to several failed attempts, maybe she’s willing to try to get more exercise. Even small changes in health behaviors can have an overall positive impact. For many chronic diseases there are several risk factors that interact (e.g., physical activity, nutrition, weight, adherence to prescribed medications), so it is important to determine where the patient is willing to start.

Motivational interviewing (MI), is a growing practice in healthcare used by trained professional, often a health coach or navigator[iii]. MI is described as “a style of being with people” as opposed to a technique that is done to a patient, and is designed for patients to receive the support needed to change[iv]. When it comes to addressing lifestyle change, some practices use a health coach role to facilitate the change process. The health coach using MI performs an assessment, identifies gaps, works collaboratively to identify goals and then uses questions and reflections that allow the patient to look at their internal motivation. MI stresses the importance of taking the time for the health provider to really listen to the values, interests, and areas that patients are ready for and are important to them. Without spending time on this, long term sustained success is challenging.

As progress is made, goals are modified or new goals are added that are now within reach. As the health coach reinforces the connection between the activities and the results, clients become more activated to incorporate behavior changes into their lifestyle going forward. They become more confident in their ability to continue to improve on their own which is a step from external to internal motivation and into the maintenance phase of behavior change. This is a very different model than what has typically been used in primary care. However, to deal successfully with chronic conditions that can be positively impacted by behavior change, practices will need to use new approaches and technology to provide the knowledge and support their patients need such as: providing health educators, health coaches or navigators, patient portals, text messaging and smart phone applications.

Sustaining change - Maintenance

Medical providers have only sporadic meetings with patients – and therefore have intermittent influence on health behavior change. Traditional models of care do not provide enough touch-points to build self-efficacy, adequately address barriers and support behavior change. Ultimately, to sustain change, motivation for healthy behaviors must shift from external (physician tells the patient what they should/should not do) to internal motivation where the patient assumes responsibility for their own health and well-being.

Again, we can learn from the example of substance abuse. Even when family, legal or job problems exert external motivation for behavior change, there is still a fundamental need for the patient to become ready for change. Change can begin with formal treatment for addiction, where education and establishment of supportive relationships serve to engage and activate the patient. The goal of treatment is to enable patients to take it forward themselves and not rely on a provider to keep them on track. Work to improve health continues well beyond the clinical setting (treatment for addiction doesn’t happen only while in a formal treatment setting; treatment is not a place) and stopping the progression of addiction depends on developing a long-term focus on eliminating undesirable behaviors and addressing barriers to positive change. The most common form of ongoing support is through sponsors and self-help groups. These groups help behavioral change to evolve from external motivation (I can’t drink) to internal motivation (I don’t drink – the patient has established a new self-definition). Patients who seek out an AA sponsor, and the knowledge, skills, and support structure to change behavior are more likely to evolve to the internal motivation needed to sustain change and achieve the overall health goal.

Patient Engagement is not one-size-fits-all

For patient engagement, we assume there is a patient: provider relationship even if it is the first time the parties have met. Regardless of whether the patient or the provider initiates a conversation about health behaviors, it is imperative that the provider make this a routine part of an office visit. An example of how this is done can be seen with pediatric EPSDT well-child visits (early and periodic screening, detection, and treatment)[v], where the health care practitioner is not only responsible for a physical examination, but also must provide “anticipatory guidance” – which supports the development of healthy behaviors. The pediatrician is charged with engaging in a partnership with the parent to develop strategies and address barriers to caring for and nurturing the young child. These types of conversations and health behavior risk assessments should continue with adult patients.

A general process flow for building a collaborative approach that will lead to patient engagement and activation can be followed and customized for each patient.

Assessment

1. Provider completes current health status/physical examination and health risk assessment of behaviors

Engagement

2. Care team initiates conversations regarding goals and priorities

3. Set goals that are patient-centered using motivational interviewing

Activation

4. Connect patient with support/assistance needed to achieve the goals

5. Patient returns to community and works to incorporate changes

Maintenance

6. Patient continues behaviors that are producing positive change and develops self-efficacy and confidence to continue

7. Provider reinforces changes that were made, encourages/suggests new ways to achieve goal

People will have individual preferences as to which lifestyle changes to address. Similarly, people like to pursue change through different mechanisms – for example, some people enjoy a support group for dieting or an exercise class, whereas others prefer a more private or solitary approach. Patient engagement is not a one-size-fits-all activity; patient health, risk behaviors, preferences, and a variety of other factors must be considered.

Using patient engagement data to take action

How can we use health information technology and data analytics to improve patient engagement? In 2012, more than half of consumers were relatively unengaged in the use of technology for healthcare[vi]. Fourteen percent of patients who had access to their physician’s website or patient portal used it compared to 43% who had access, but did not use it and 44% who reported not having access at all5. Overall, the survey found that patients used health information technology less often than they used technology for purposes such as banking or shopping, and the study noted generational differences in how patients prefer to use technology to interact with their care provider. Today, more patients are becoming engaged and their expectations for using technology to manage their health are increasing. Leading healthcare systems are using patient portal technology to meet Meaningful Use criteria and to boost patient engagement[vii]. Portal technology can be used to educate patients and personalize care, as well as offer ways for patients to be actively involved through home monitoring and self-management tools.

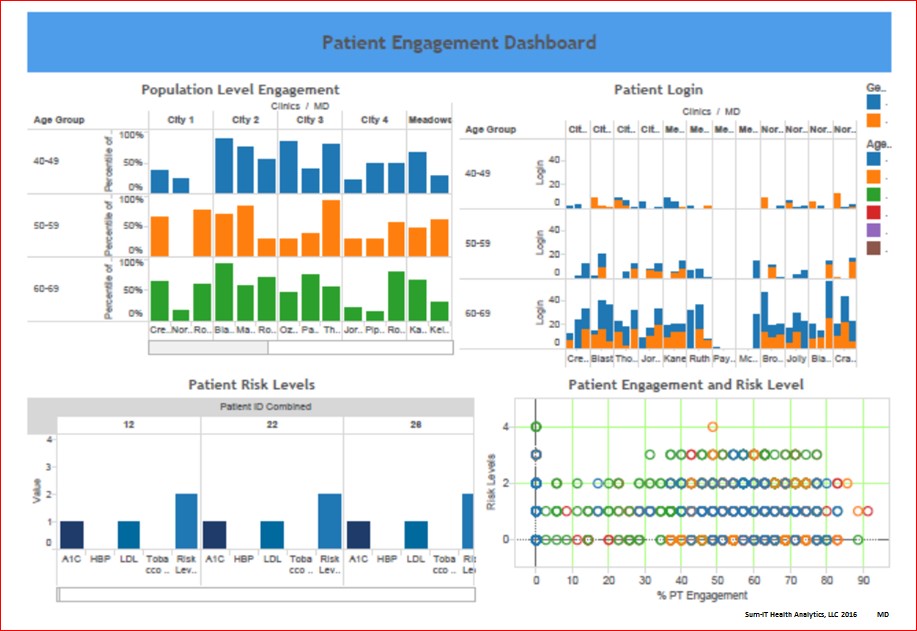

Providers need data beyond what is currently provided in EMR problem lists. To collaborate with patients on managing chronic conditions, they need information on patient health behaviors and risk factors. Providers can better understand the health of their population by creating registries and using analytics to align practice resources with patient needs. For example, high risk patients with uncontrolled diabetes may need certified diabetes educators. It may be beneficial to collect patient home glucose monitoring data through the portal, or to have a nurse available to talk with patients when there are early warning signs that urgent care may be needed. This data may be presented through a dashboard where care teams can dynamically view their patient panel and target interventions quickly.

Integrating patient engagement data with clinical data can reveal clues that will assist care teams to move patients to higher levels of engagement and activation. It is useful to understand how the patient is using the portal – are they viewing test results, scheduling appointments, or refilling prescriptions? Patients might send questions to their care team through the portal or submit home monitoring data, indicating a higher level of engagement. Providers can benefit from patients reaching higher levels of engagement if they consider patient-generated data as valid and valuable in providing a holistic view of the patient. Additionally, use of patient-reported outcomes such as controlled glucose levels and medication adherence have been shown to enhance patient engagement when providers and patients use this information in conjunction with symptoms or clinical findings, and collaborate on health goals[viii]. It may also be of interest to include patient satisfaction data to better understand issues and barriers to health outcomes.

Figure 3. Patient Engagement Dashboard

Patients need data to help them decide where to focus their efforts. Patients are looking for ways to improve their health. A message from a health care provider that correlates the findings from the patient examination to health behaviors is a powerful change message. Patients increasingly want to use technology to track and share health information. For example, the ability to trend blood pressure, laboratory test or body mass index (BMI) data over time is helpful for self-monitoring – where patients obtain objective data that answers the question, “How am I doing?” This is no different from consumer desires to understand personal financial data when planning for retirement. These data are motivating, and reinforce patient efforts to change (e.g., Efforts to reduce my blood pressure by getting more exercise and taking my medication regularly are showing results!). Many patients are interested in working with their providers to share data they have collected through home monitoring.

Patients also need a simple and effective way to ask their provider for additional help – if they are struggling with change, or experiencing problems with a recommended change, they need to access their care team through a patient portal, or dial-a-nurse, or other easy method of provider messaging. Patients can’t wait until the next regularly scheduled visit to address problems in improving health behaviors. Patients may need referrals to community resources that can help them address the desired health behavior changes. Providing solutions through both data and technology will increase patient engagement and support behavior change.

Conclusions

Ultimately, a collaborative approach is needed to engage and activate patients to take ownership for changing their health behaviors. Models such as the Transtheoretical Model of Change can inform efforts to develop a method that is both repeatable and adaptable to individual patient preferences and needs. Developing care teams that support patients to initiate change and then become internally motivated to sustain their behavior changes is a key to success. This will be an enormous cultural change for healthcare and we are only now starting to realize the extent of the change needed. Finally, using analytic solutions to measure and monitor patient engagement can assist care teams and patients by facilitating the communication and collaboration needed to achieve healthier outcomes.

How We Work with Clients

At Sum-IT Health Analytics, we use a public health approach to help our clients become data-driven and engage in transformative interventions. Our leadership team has extensive experience in public health, consumer and patient engagement, performance measurement, and change leadership. We create custom analytic solutions to address key patient engagement and population health metrics. This targeted approach helps our clients to quickly use their data for interventions; furthermore, we identify additional data sources that can provide insight into refining patient engagement strategies. Analytics will reveal opportunities for taking action to impact health quality, outcomes, and patient experience while identifying efficiencies in the delivery of services. Our focus is to make your mountain of information accessible and understandable to health experts and decision-makers so it can be translated into action. In today’s rapidly-evolving healthcare marketplace, payer incentives and penalties are changing rapidly – the time to act is now!

Contact us to learn more about how we can collaborate with your organization to improve patient engagement, activation, and outcomes.

The authors would like to thank Daniel Addison and Mila Smith for their work on the Patient Engagement Dashboard and June Wilwert and Rebecca Lang for sharing their insights on behavior change.

Contact Sum-IT or the authors at:

Miriam Isola DrPH, CPHIMS, Miriam.Isola@sumithealthanalytics.com

Kathy Schneider, PhD, Kathy.Schneider@sumithealthanalytics.com

[1]Prochaska, J and DiClemente, C. (1983) Stages and Processes of Self-Change in Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 5: 390-395.

[ii] Hibbard, JH and Greene, J (2013) What the Evidence Shows About Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes and Care Experiences; Fewer Data on Costs. Health Affairs, 32(2): 207-214.

[iii] Evdokimoff, M. (2016, March) Patient Activation Using Technology-Supported Navigators. Presentation at Annual Health Information Management Systems Society meeting. Las Vegas, NV.

[iv] Miller W. and Rollnick S. (2012). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, (Applications of Motivational Interviewing), 3rd Edition. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

[v] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2005).Policy Statement. Organizational Principles to Guide and Define the Child Health Care System and/or Improve the Health of All Children. Pediatrics, 116(1): 274-280. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/116/1/274.full.pdf

[vi] Deloitte 2012 Survey of U.S. Health Care Consumers. Retrieved from: http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/us-lshc-consumers-and-health-it.pdf

[vii] Weinstock, M. Healthcare’s Most Wired 2015. Hospitals and Health Networks. Retrieved from: http://www.hhnmostwired.com/winners/PDFs/2015/MostWired_2015_winners.pdf.

[viii] Danielle C. Lavallee, Kate E. Chenok, Rebecca M. Love, Carolyn Petersen, Erin Holve, Courtney D. Segal and Patricia D. Franklin. Incorporating Patient-Reported Outcomes Into Health Care To Engage Patients And Enhance Care. Health Affairs 35, no.4 (2016):575-582.